Deploying U.S. government civilians to difficult and dangerous places is nothing new. Plaques to fallen colleagues in the lobbies of the Department of State and USAID remind us of those who have died in overseas operations. However, in recent years our nation has asked a lot more of our civilian government personnel, and not only in Iraq and Afghanistan.

On April 14, the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Subcommittee on Oversight of Government Management, the Federal Workforce, and the District of Columbia (HSGAC/OGM) will hold a hearing on personnel benefits and support for deployed civilians in combat zones. This follows on the inquiries by Government Accountability Office, the House Armed Services Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, and the House Committee on Government Oversight and Reform Subcommittee on Federal Workforce, Postal Service, and the District of Columbia.

The New Normal

Today, many embassies remain open under security situations which, in the past, would have led to certain closure. More posts are at risk of attack in spite of the unwelcoming “fortress America” building standards. Civilians have deployed embedded within military units. An increasing proportion of assignments are so dangerous that families do not join employees overseas. The number of posts qualifying for hardship and danger pay has increased. The scope and scale of civilian engagement has expanded, placing greater numbers and types of employees at risk.

And more names have been added to the plaques.

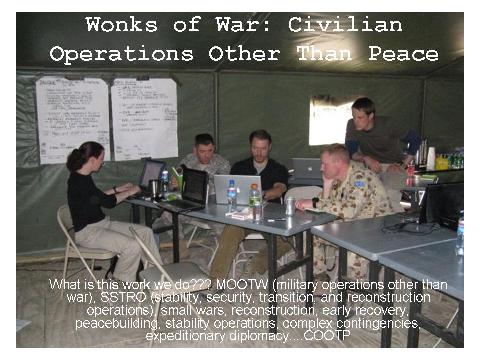

The decisions to send civilians to these missions have been made, in spite of their cost, because of the absolute centrality of civilian diplomacy and development to today’s missions. The history of PRT deployments – and more importantly, experiences where the military has had limited access to civilian advisors and partners – demonstrates this powerfully. Their presence is equally vital to the international community’s legitimacy and effectiveness in lesser-known engagements in places like Darfur and Eastern Congo. Even in traditional posts, like those in Pakistan and Mexico are increasingly dangerous as recent attacks have tragically proven.

These assignments are becoming the “new normal,” and have broad implications for recruitment, training, support, medical care, benefits, incentives, and career paths within the Foreign Service and the civil services of many departments. They also raise serious questions about the roles of diplomats and development professionals in non-permissive environments, and how to manage risk while increasing access to populations and environments that are critical to U.S. engagement.

Key Congressional Questions

The upcoming HSGAC/OGM hearing, and follow-up work on legislation and requisite funding, should wrestle with a few key areas.

No comments:

Post a Comment